In this section we start looking at Object-Oriented Programming , objects, classes, inheritance, etc.

So far we have create basic Objects that contain properties, these properties have four attributes

- Configurable - I can modify the behavior of the property, so I can make them non-enumerable, non-writable or even non-configurable

- Enumerable - Indicates if the property will be returned in a for-in loop

- Writeable - Indicates if the property’s value can be changed

- Value - Contains the actual data value for the property.

| Changing a properties attribute | let person = {};

Object.defineProperty(person, "name", {

writable: false,

value: "Paul"

});

console.log(person.name); // "Paul"

person.name = "Will"; // won't do anything as propery is read-only (not writeable)

console.log(person.name); // "Paul" |

We can access Object's Properties by using the dot notation or the bracket notation. These are called accessor properties. Javascript introduced Getter and Setters properties, they are basically functions only for which are responsible for getting and setting a value.

- Configurable - I can modify the behavior of the property, so I can make them non-enumerable, non-writable or even non-configurable

- Enumerable - Indicates if the property will be returned in a for-in loop

- Get - when you need to read the proerty

- Set - when you want to set a property

| Accessor properties example | // Define object with pseudo-private member 'year_' and public member 'edition'

let book = {

year_: 2017,

edition: 1

};

Object.defineProperty(book, "year", { // Year is the property, the block is the accessor properties

get() {

return this.year_;

},

set(newValue) {

if (newValue > 2017) {

this.year_ = newValue;

this.edition += newValue - 2017;

}

}

});

book.year = 2018;

console.log(book.edition); // Edition is now 2 |

| Defining multiple properties | // Same as above

let book = {};

Object.defineProperties(book, {

year_: {

value: 2017

},

edition: {

value: 1

},

year: {

get() {

return this.year_;

},

set(newValue) {

if (newValue > 2017) {

this.year_ = newValue;

this.edition += newValue - 2017;

}

}

}

}); |

| Read a property | let descriptor = Object.getOwnPropertyDescriptor(book, "year_"); console.log(descriptor.value); // 2017 console.log(descriptor.configurable); // false console.log(typeof descriptor.get); // "function" |

Javascript has the === operator but in some cases it was insufficient, so recently they added Object.is() which behaves the same way but handles these odd cases

| Object identity and equality | console.log(Object.is(true, 1)); // false

console.log(Object.is({}, {})); // false

console.log(Object.is("2", 2)); // false

// Correct 0, -0, +0 equivalence/nonequivalence:

console.log(Object.is(+0, -0)); // false

console.log(Object.is(+0, 0)); // true

console.log(Object.is(-0, 0)); // false

// Correct NaN equivalence:

console.log(Object.is(NaN, NaN)); // true |

You can destructure objects easily using the below

| Object destructuring | let person = {

name: 'Paul',

age: 21

};

let { name: personName, age: personAge } = person;

console.log(personName);

console.log(personAge);

--------------------------------------------------------------------------

// You can take this even further and even use default values if a property is not defined

let person = {

name: 'Paul',

age: 21

};

let { name, age, job='Developer' } = person;

console.log(name);

console.log(age);

console.log(job); // Software engineer

|

We have seen how to create objects using the object constructor and the object literal way there are two design patterns that can also be used used, factory pattern and the function constructor pattern (very Java like)

In this section I cover Object creation before ES6 which has more implemented classes and inhertaince, which uses prototyping to create classes and use inheritance.

| Factory Pattern | function createPerson(name, age, job) {

let o = new Object();

o.name = name;

o.age = age;

o.job = job;

o.sayName = function() {

console.log(this.name);

};

return o;

}

let person1 = createPerson("Paul", 21, "Developer");

let person2 = createPerson("Will", 50, "Actor"); |

| Function Constructor Pattern | // The above rewritten as Function Constructor Pattern

// Note the Function name is in UPPER case

// let Person = function(name, age, job) { // You can also use this way as well for below line

function Person(name, age, job){

this.name = name;

this.age = age;

this.job = job;

// this function will be created many times if you create many Person objects

// once for each object which is a problem with constructor patterns (see below for better option)

this.sayName = function() {

console.log(this.name);

};

}

// Note we use the new operator

let person1 = new Person("Paul", 21, "Developer");

let person2 = new Person("Will", 50, "Actor"); |

| Function Constructor Pattern (enhanced) | // The sayName function is only created once and thus multiple Person objects share the same function

function Person(name, age, job){

this.name = name;

this.age = age;

this.job = job;

this.sayName = sayName; // now points to the function sayName()

}

function sayName() {

console.log(this.name);

} |

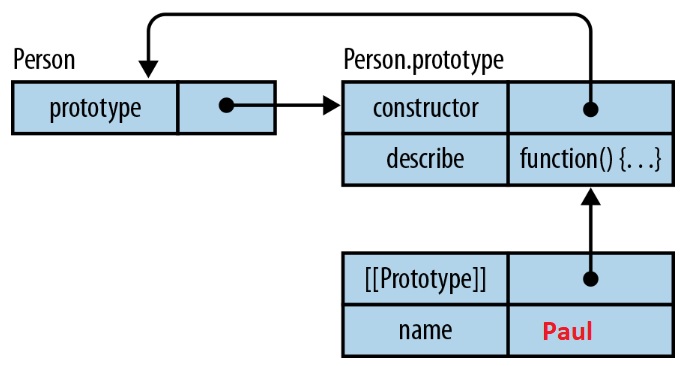

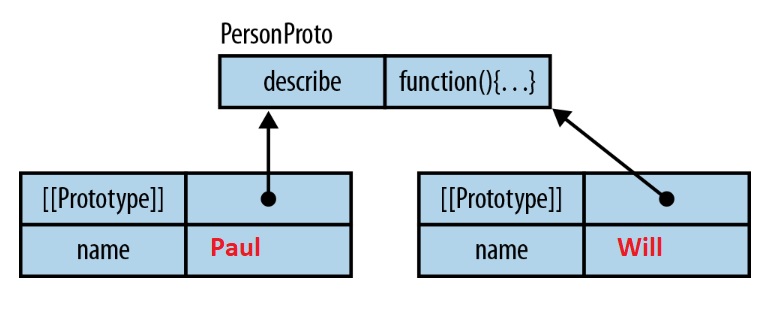

Using the prototype pattern each function is created with a prototype property which is a object containing properties and methods that will be available to instances of a reference type. The benefit of a prototype is that its properties and methods are shared will all created instances meaning no additonal resources are created for each object.

| Prototype Pattern | let Person = function (name, age, job){

this.name = name;

this.age = age;

this.job = job;

}

// This is shared among all created Person objects

Person.prototype.sayName = function() {

console.log(this.name);

}

let person1 = new Person("Paul", 21, "Developer");

console.log(person1);

person1.sayName(); |

The Person Object has a prototype object, this object is the same object for all Persons and thus any data (properties/methods) are shared between all the Person Objects created, in our case in the example above we put the function SayName() function which will be shared among all Person Objects.

|

|

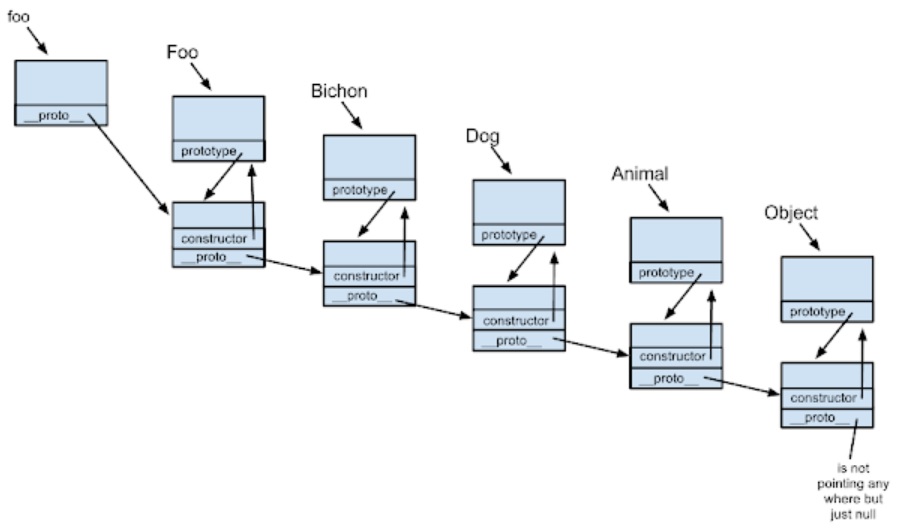

Javascript supports implementation inheritance which means properties and methods will be inherited, prototype chaining is used to implement inheritance, basically the prototype points to another instance of another type this means it has a pointer to another constructor, this can continue to multiple inheritance, you can see how this works in the image below

| Inheritance basic example | //Super Class Pet

function Pet() {

this.name = "";

this.type = "";

}

Pet.prototype.getPetName = function() {

console.log("Pets Name: " + this.name);

};

Pet.prototype.talk = function(speak) {

console.log("Pet talking: " + speak);

};

Pet.prototype.getType = function() {

console.log("Pet type: " + this.type);

}

// Subclasses Dog and Cat

// Create Dog and inherit from SuperType

function Dog() {

this.type = "Canine"

}

Dog.prototype = new Pet();

// override existing method and call super method

Dog.talk = function (speak) {

this.talk(speak);

};

// Create Cat and inherit from SuperType

function Cat() {

this.type = "Feline"

}

Cat.prototype = new Pet();

// override existing method and call super method

Cat.talk = function (speak) {

this.talk(speak);

};

// Main

let rover = new Dog();

rover.name = "Rover"

rover.getPetName();

rover.talk("Woof Woof!!"); // example of passing arguments

rover.getType();

let felix = new Cat();

felix.name = "Felix"

felix.getPetName();

felix.talk("Meow Meow!!"); // example of passing arguments

felix.getType(); |

There is a technique called constructor stealing, basically you call the supertype's constructor from within the subtype's constructor

| Constructor Stealing | function SuperType(name){

this.name = name;

}

function SubType() {

// inherit from SuperType passing in an argument

SuperType.call(this, "Paul");

// instance property

this.age = 21;

}

let instance = new SubType();

console.log(instance.name); // "Paul";

console.log(instance.age); // 21 |

Lastly on inheritance there are a number of other techniques that can be used, I highlight them here

- Combination Inheritance - combines prototype chaining and constructor stealing to get the best of each approach.

- Prototypal Inheritance - allow you to create new objects based on existing objects without the need for defining custom types.

- Parasitic Inheritance - create a function that does the inheritance, augments the object in some way, and then returns the object as if it did all the work.

- Parasitic Combination Inheritance - combines parasitic and combination techiques

| Combination inheritance | function SuperType(name){

this.name = name;

this.colors = ["red", "blue", "green"];

}

SuperType.prototype.sayName = function() {

console.log(this.name);

};

function SubType(name, age){

// inherit properties

SuperType.call(this, name); // constructor stealing

this.age = age;

}

// inherit methods

SubType.prototype = new SuperType();

SubType.prototype.sayAge = function() {

console.log(this.age);

};

let instance1 = new SubType("Paul", 21);

instance1.colors.push("yellow");

console.log(instance1.colors); // "red,blue,green,yellow"

instance1.sayName(); // "Paul";

instance1.sayAge(); // 21

let instance2 = new SubType("Will", 50);

console.log(instance2.colors); // "red,blue,green"

instance2.sayName(); // "Will";

instance2.sayAge(); // 50 |

| Prototypal inheritance | let person = {

name: "Paul",

friends: ["Will", "Moore", "Graham"]

};

let anotherPerson = Object.create(person); // we use the Object.create() method

anotherPerson.name = "Arthur";

anotherPerson.friends.push("Norman");

let yetAnotherPerson = Object.create(person); // we use the Object.create() method

yetAnotherPerson.name = "George";

yetAnotherPerson.friends.push("Basil");

console.log(person.friends); // "Will, Moore, Graham, Arthur, Basil" |

| Parasitic inheritance | function createAnother(original){

let clone = object(original); // create a new object by calling a function

clone.sayHi = function() { // augment the object in some way

console.log("hi");

};

return clone; // return the object

}

let person = {

name: "Paul",

friends: ["Will", "Moore", "Graham"]

};

let anotherPerson = createAnother(person);

anotherPerson.sayHi(); // "hi" |

| Parasitic combination inheritance | function inheritPrototype(subType, superType) {

let prototype = Object(superType.prototype); // create object

prototype.constructor = subType; // argument object

subType.prototype = prototype; // assign object

}

function SuperType(name) {

this.name = name;

this.colors = ["red", "blue", "green"];

}

SuperType.prototype.sayName = function() {

console.log(this.name);

};

function SubType(name, age) {

SuperType.call(this, name);

this.age = age;

}

inheritPrototype(SubType, SuperType);

SubType.prototype.sayAge = function() {

console.log(this.age);

};

let person1 = new SubType("Paul", 21);

person1.sayName();

person1.sayAge();

console.log(person1.colors); |

We take a in depth look at classes which were introduced in ES6, although easier to use behind the scenes they still use prototype and constructor concepts, so understanding the above section is worth while. There are two ways to create a class

| Create class | // class declaration

class Person {}

// class expression

const Person = class {}; |

A class can have constructor, instance variables, instance methods, getter/setter accessor methods and static class methods, this is very similar to Java.

| Class example | const Person = class {

constructor(name, age) {

this._name = name || null; // can use defaults

this._age = age;

}

// Getter and Setter accessor methods

get name() {

return this._name;

}

set name(value) {

this._name = value;

}

get age() {

return this._age;

}

set age(value) {

this._age = value;

}

toString() {

console.log(this.name + " " + this.age); // calling the get name() and get age()

}

// a static method use Person.sayHello() to invoke

static sayHello() {

console.log("Hello World!");

}

}

let person1 = new Person("Paul", 21);

person1.toString();

console.log(person1.name); // use the get name() method |

Class inheritance is much much easier than ES5, as it fully supports inheritance in a more friendlier way.

| ES6 class basic example | class Pet {

constructor(name, type) {

this.name = name;

this.type = type;

}

// Getter & Setter accessor method here, excluded to keep code short

// inherited by all sub classes

toString() {

console.log("Pet name is " + this.name + " and is a " + this.type);

}

}

class Dog extends Pet {

constructor(name, type, color) {

super(name, type); // calling super constructor (Pet), should be first command

this.color = color;

}

// Dog class own method

talk() {

console.log(this.type + " goes Woof Woof!!");

}

}

class Cat extends Pet {

constructor(name, type, color) {

super(name, type); // calling super constructor (Pet), should be first command

this.color = color;

}

// Cat class own method

talk() {

console.log(this.type + " goes Meow Meow!!");

}

}

let rover = new Dog("Rover", "Dog", "Brown");

let felix = new Cat("Felix", "Cat", "Black");

rover.toString();

felix.toString();

rover.talk();

felix.talk(); |

| Abstract Class example (work around) | // ES6 does not fully support Abstract classes but here is a work around

// Abstract base class

class Vehicle {

constructor() {

if (new.target === Vehicle) {

throw new Error('Vehicle cannot be directly instantiated');

}

if (!this.foo) {

throw new Error('Inheriting class must define foo()');

}

console.log('success!');

}

}

// Derived class

class Bus extends Vehicle {

foo() {}

}

// Derived class

class Van extends Vehicle {}

new Bus(); // success!

new Van(); // Error: Inheriting class must define foo() |

One feature with Javascript is that you can extend built-in class as well and you can do multiple inheritance (not fully supported but have a work around)

| Inheriting from Built-in types | class SuperArray extends Array {

shuffle() {

// Fisher-Yates shuffle

for (let i = this.length - 1; i > 0; i--) {

const j = Math.floor(Math.random() * (i + 1));

[this[i], this[j]] = [this[j], this[i]];

}

}

}

let a = new SuperArray(1, 2, 3, 4, 5);

console.log(a instanceof Array); // true

console.log(a instanceof SuperArray); // true

console.log(a); // [1, 2, 3, 4, 5]

a.shuffle();

console.log(a); // [3, 1, 4, 5, 2] |

| Class mixins | class Vehicle {}

let FooMixin = (Superclass) => class extends Superclass {

foo() {

console.log('foo');

}

};

let BarMixin = (Superclass) => class extends Superclass {

bar() {

console.log('bar');

}

};

let BazMixin = (Superclass) => class extends Superclass {

baz() {

console.log('baz');

}

};

function mix(BaseClass, ...Mixins) {

return Mixins.reduce((accumulator, current) => current(accumulator), BaseClass);

}

class Bus extends mix(Vehicle, FooMixin, BarMixin, BazMixin) {}

let b = new Bus();

b.foo(); // foo

b.bar(); // bar

b.baz(); // baz |